Where Have All the Sparrows Gone?

– to Disney!

By Diane Barile, South Brevard Historical Society

The wild marshes of the St. Johns River lazed on a leisure expanse, a miniature Florida Everglades between Cocoa and Orlando, Florida. Scientist Suzanne Bayley plowed the bow of the motor launch into a spartina, wire grass tussock, rather far from the island of trees set in the sea of grasses, a hard wood hammock.

“Come on,” she said, “we get out here.” We waded the rest of the way. “Unlock one of the oars and hand it to me,” she called over her shoulder as she slogged through black sticky muck and knee-deep water.

I am a reluctant slogger but over the gunnel I went. Halfway between the boat and the tree island I asked, “Why are you carrying that oar? Should it not stay in the boat?”

“No,” she assured me, “it’s to bat away any water moccasins coming after us.” I became a rapid slogger.

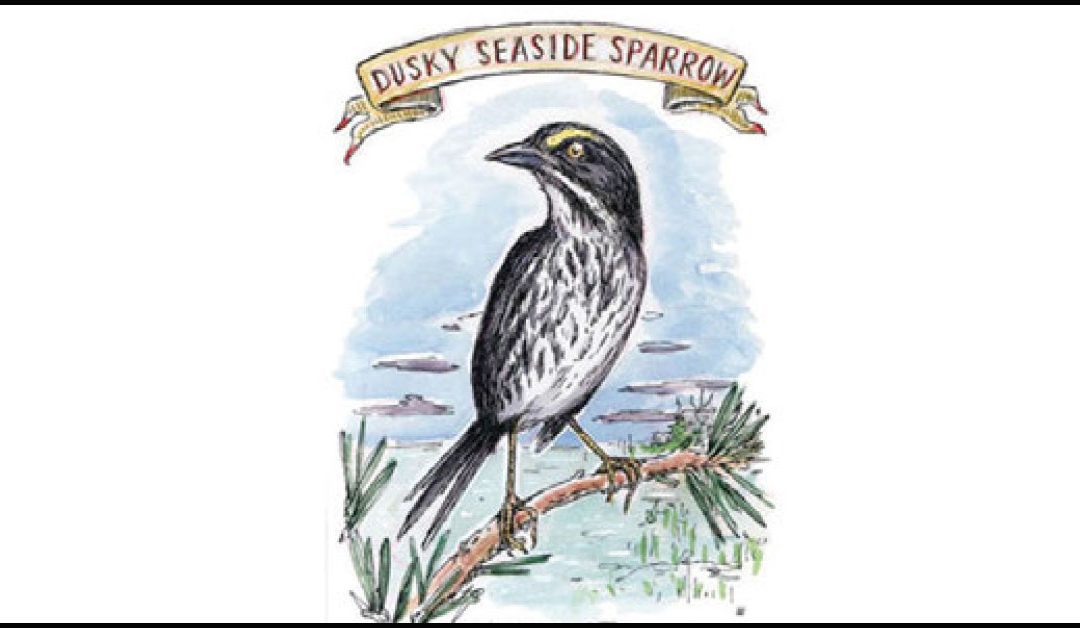

Dr. Bayley was hoping to hear, or perhaps see, a Dusky Seaside Sparrow, a bird found only in these wetlands. We did get back to the launch safely but no moccasins and no Dusky. Dr. Herb Kale, orthologist, had been charting their demise for some time, as did scientists, for the Canaveral National Seashore on Merritt Island.

The tiny, shy Duskies were originally found only in the salt marshes of Merritt Island and fresh marshes of the St. Johns River west of Cocoa and Titusville. Food and nesting for Duskies depended on the precise configuration of flooded marsh plants. In the twentieth century, Duskies were set upon by a large invasive species. Human incursion in a blossoming agricultural economy, wetlands were described as wastelands to be improved for crop yields and human habitation.

While the Dusky Seaside Sparrow depended on a limited and specific environment people could, and did, alter living space to their needs. Settlers faced formidable challenges: (1) heat, (2) land under water or prone to flooding, and (3) mosquitoes.

Conquering heat had to wait for available air conditioning to beat the heat, but wetlands and mosquitoes were related to existing skills in water management. Canals and ditches lowered surface water and pulled the wet out of wetlands. Thus, there were farms, groves, and homes safe from flooding.

Mosquitoes breed in small shallow pools of water. Drainage decreases mosquito breeding and larval development. Similarly, mosquitoes do not breed in deeper water. Along the Indian River Lagoon some saltwater wetlands were flooded to eliminate mosquito habitat. There were fewer mosquitoes hatched but Dusky were soon gone completely.

During World War II trials for the insecticide DDT were conducted on the barrier island with consequences across many species. The human species thrived with each “improvement” to the demise of our reclusive sparrow. The Duskies dwindled first on Merritt Island. Then they were found only west of Cocoa where Dr. Bayley and I slogged in 1975.

The swan song for the Dusky Seaside Sparrow came with the construction of the Beeline Expressway (now called the Beachline). The four-lane highway sliced through the last Dusky habitat. The bird population decreased almost before scientists noticed.

By 1979 only seven males survived, six were captured, and just like sports heroes, the six went to Disney World’s Wild Kingdom. Breeding with the related Scott Seaside Sparrow was unsuccessful. The last Dusky died in 1987. Dr. Bayley moved to Alaska to race sled dogs. Dr. Kale died too soon. No one listens for the Dusky Seaside Sparrow anymore and I haven’t slogged in a long, long time.

Recent Comments