Territorial Florida’s East Coast Remembered

By: Diane D. Barile and Michael Barile, South Brevard Historical Society

The United States owned the world’s supply of wood in greatest demand for shipbuilding. These Southern Live Oak trees (Quercus Virginiana), were seen as an asset when Florida was accepted into Statehood in 1841.

Live Oak pirates and poachers from England, France and Spain regularly and illegally cut and carried off trees to supply vital parts for foreign naval vessels. For centuries the English timbered from Virginia through Georgia. Throughout Florida to Louisiana the live oak pirates decimated the public lands. Spain maintained its naval and commercial vessels but did little to prevent pillage of its vast coastal forests.

Then it all changed with the American Revolution. In 1794, President Washington established the US Navy, and ordered six American built frigates to protect American commercial shipping in the Mediterranean threatened by pirates from the African Barbary Coast. During the War of 1812, one of the new frigates, the Constitution, successfully repelled cannon bombardment as the cannonballs bounced off the sides of the ship. It was there after known as Old Ironsides, even though it had no iron, just live oak sheathing and live oak internal braces.

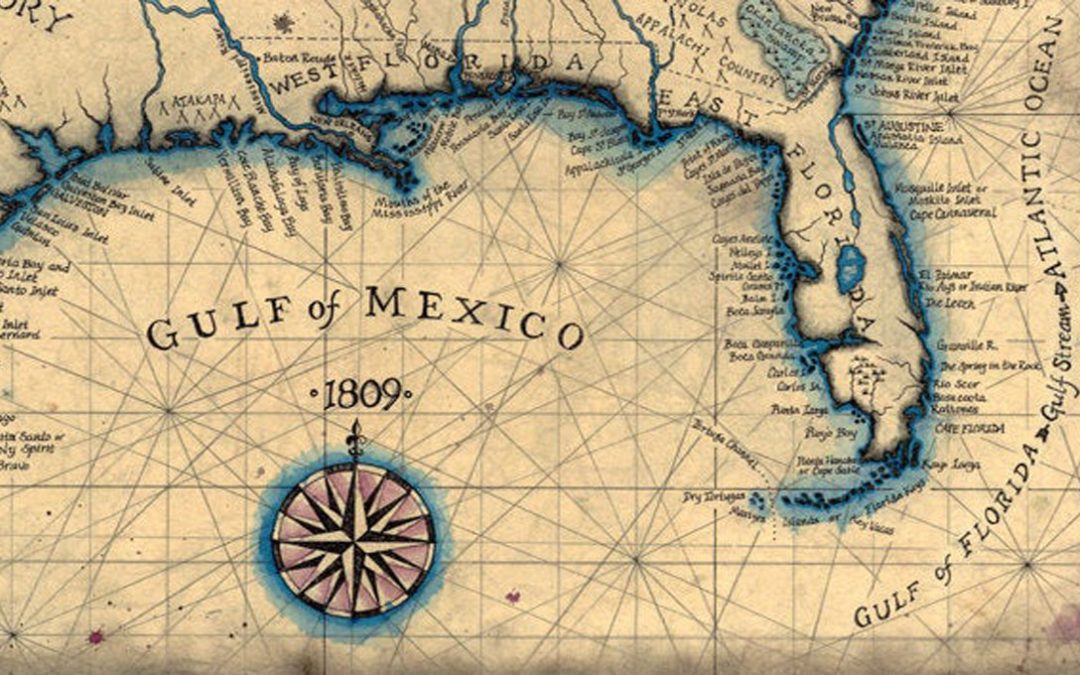

The race was then on for the remaining Live Oak trees in Florida. Some loyalist in Georgia even shipped trees to the West Indies for English ships. Unprotected rivers were open to illicit forestry by nations worldwide. Florida, first a territory in 1821 and a state in 1841, held the last virgin stands of the coveted Southern Live Oak. Congress passed legislation making live oak lands federal property to assure a continued supply of “ship construction timber” for our Navy.

American shipbuilding expertise found that coastal grown live oaks produced a stronger and denser wood with less sap and finer grain than those found farther inland. Whaling ship builders having depleted the near shore whale population were forced father worldwide and for longer voyages. An 1826 survey along the Atlantic Coast in Florida, reported more than half of all live oaks were gone as far as 15 miles inland. The take of Live Oak trees had expanded due to the demand from whaling, the US Navy, commercial shipbuilders and trade.

Florida statehood did not come without trauma. Chased south from Georgia and Alabama by advancing Americans, the Seminole Indians fought back in a series of wars. To form a buffer between the Seminoles and Florida coastal development, settlers were given free live oak rich land along the Indian River. An assigned US Revenue Agent was posted to collect a tax for each of the nation’s oaks felled. With the final removal or banishment of the native people, lumbering exploded along the St Johns River and Indian River Lagoon.

Winter in Florida was no vacation for the team of men contracted by New England ship builders to harvest live oaks. These “Live Oakers” were housed in large camps with up to fifty tree cutters, sixty carpenters and supporting staff. Team leaders came with specific orders for rough board lengths. Most difficult however, were orders for braces and brackets made from specified natural angles of branch to trunk joints. These were used to stabilize the inner and outer sheathing of the hull. Whole trees could be cut down just because one branch angle met design specifications.

The camps became small towns each winter with work crews scouting coastal lagoons. Oak Hill in Volusia County became a year round settlement as some of the “Oakers” became permanent Floridians. Construction of Whalers, American Navy and Clipper ships again pressured and heightened competition for the live oak supply. Coastal Red Cedar tree stands were also timbered for ship decking and pencils.

Wars bring innovation. The Civil War, 1861-1865, produced metal clad vessels. The “Iron Clads”, the Confederate Merrimack (Virginia) and the Union Monitor set the precedent and relieved dependence on the last remaining live oaks. Even today it is unusual to find ancient oaks along the lagoon.

But some live oaks survived. The last surviving Whaling ship, harbored at Mystic Seaport, Connecticut, the Charles W Morgan was in need of major repairs. Some of the live oaks missed by the 19th century “Live Oakers” met their demise in the hurricanes of 2005. Ship designers and craftsmen at Mystic Seaport hired huge trucks to collect downed oaks to refurbish the Morgan. The legacy of the mighty Southern Live Oaks of the Indian River Lagoon lives on in the Charles W Morgan, the last of the whalers.

Recent Comments