Tom Tiger and the Last Canoe

By Diane Barile, South Brevard Historical Society

He set out simply to build a canoe. The leader of the Cow

Creek band of Seminoles, living north of Lake Okeechobee, he was an icon of the tribe to white Floridians. But, to the native Americans he was a friend and respected leader. In 1900, the fate of Tom and the canoe brought an audacious scam and enlightened consternation, then support by the white community for Tom and his people.

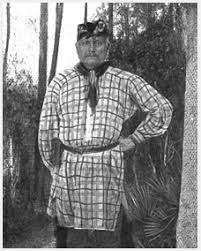

Tom was an impressive man, both physically and humanly. Known as Captain Tom or Tom Tiger by white settlers, in reality he was a Micco Tuestenugee War Chief. He did fight with his tribe in the Third and last Seminole War. In the aftermath of the fighting in 1859, Tom kept the defeated and disposed Cow Creek clans together. Trade was established with white homesteaders on the central Florida Coast, bartering or selling venison, berries, and hides for supplies. With few English words, Tom was able to build amicable relationships with neighbors and further provided for a peaceful existence.

Physically, Tiger was six feet tall, stately, muscular, clever and courageous. “Good mannered”, said the settlers who held him in high regard and comradeship. For example, in 1872 when the steamship “Victor” ran aground at Jupiter Inlet carrying a cache of liquor, Tom joined a group of riotous settlers in an all-night drinking bout. Those friends also helped Tom set a legal precedent. When a white man made off with one of Tom’s horses, settlers helped him become the first Native American to take a white man to court for damages. When U.S. President Arthur visited Kissimmee, Florida, Tom was leader of the Welcome Committee.

Canoes were essential to the Seminoles for transport of families and supplies across the grassy Everglades and wet prairies. The process of preparing a new canoe was a studied, prolonged, and respected art within the tribes. Few men had the talent or experience to hand craft these shallow, draft vessels. Tom Tiger and Charlie Cypress of the Everglades Miksuki Seminoles were two such masters.

In building the canoe, the first challenge for Tom was to find the right tree, one with the heartwood located to the side of the trunk rather than the usual center. He searched from Lake Okeechobee, to a cypress strand in southwest Brevard County (part of St. Lucie County today). Once selected, the tree was cut, hewn, and roughly shaped before being buried in the mud for eighteen to twenty-four months.

Upon return, Tiger allowed the tempered log to air for a few weeks. Then, the final shaping of the canoe began. He would carefully burn away some of the wood, then chisel by axe to a uniform thickness. The final step would have been with a helper, who would tap the side of the boat while the master listened for a distinct vibration in the proper pitch indicating optimal thickness and strength. Tom Tiger did not finish his canoe.

His family searched for their father and leader. They found him dead, axe still in his hand, killed by a lightning strike. The loss felt by his wives, children and clan, was unfathomable. Tom Tiger, Micco Tuestenugee, was buried where they found him, his last canoe set to flames above his grave. Places of death were sacred to the tribe, never to be disturbed. Well, not so.

The extraordinary life of the War Chief had one more chapter of notoriety. J.L. Flourney, a white man from Johnstown, Pennsylvania, posed as an historian from the Smithsonian Institute, and paid some local men to take him to Tom Tiger’s burial site. After uncovering the bones and some of Tom’s personal relics, Flourney stowed the finds in his hunting coat and set off north. Some say he wanted the bones for his museum. The Smithsonian disavowed any relationship with the man other than refusing to buy some bones Fourney offered for sale.

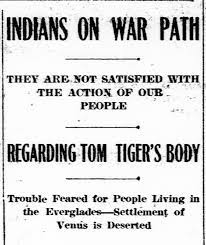

In Florida, the situation took a more severe tone. The leaders of the Cow Creek clan sent a message into Fort Pierce:

“BRING BACK BONES OF OUR

BEST FRIEND, OR WE WILL FIGHT,

AND PLENTY WHITE PEOPLE WILL DIE”

Seminole leader Billy Smith warned: “One moon to bring our friend home.”

Newspapers across the state, the St. Lucie Tribune, the Ocala Evening Star and others ran the story. The state legislature allotted $300 for the return of Tom Tigers skeleton. The Pensacola Journal called the whole affair, “revolting to every sense of decency and right morals.” Closer to home the sentiment was seen as an affront, and further, the long-maintained peace endangered! Some believed a new Seminole War was eminent.

In 1907, a rumor was circulated that the Seminoles on Fisheating Creek killed the Sheriff, which would have given Bob Marley’s, “I shot the Sheriff” new meaning to the Seminoles. Local investigations of the incident, dragged on slowly. Then, at the end of April, there was a new message from the Seminoles:

“ALL BIG LIE OF WHITE MAN.

INDIAN NO FIGHT.

CANNOT FIGHT WHITE MAN.

INDIANS GOT NO MONEY.

CAN’T FIGHT NO HOW.”

Finally, in July, Mr. Flourney quietly returned the bones and belongings to Tom Tiger’s sacred burial place, and promptly hightailed to the first train out of town.

Perhaps the incident could be seen as a proper legacy for a truly great man. He courageously led his people through a crippling defeat, to an amiable, if not cautious peace, with the fast-expanding settlements of the white man. In his death, the former foes from the Seminole Wars, were among the first to acknowledge a moral and righteous concern for their Native American friends.

Tom Tiger, Micco Tuestenugee, fought the good fight with his comrades. In defeat he brought peace among his own people, the Cow Creek Seminoles and the white man.

Recent Comments